How the Finns tied their destiny to the Daugava River

The June 26, 1941, issue of the German occupation-era magazine Laikmets begins with a story about the fording of the Daugava River dedicated to the first anniversary of the capture of Riga and continues with the acknowledgement that Finland is the land of heroes in the north: "Side by side with Germany, Finland is still today fighting the Bolshevik enemy of the world. From Lake Ladoga to Petsamo harbor on the shores of the Arctic Sea, the Finnish army stands side by side with German troops in the northern part of the longest front the world has ever seen, and together they are winning victory after victory."

This is not written in black and white in the magazine, but the juxtaposition of the two themes adds credibility to the claim that the Germans' ability to ford the Daugava was one of the preconditions set by the Finns for their entry into the World War on the German side. Nor is there any document by which Germany and Finland divided territories or responsibilities on the model of the agreement between Germany and the Soviet Union known as the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. The decisive proof of Finland's claim is the conduct of Germany and Finland as if there had been such a claim. The publication in the magazine Laikmets is only circumstantial evidence of such a link, but there is plenty of it. Even more numerous than the evidence are the references in which historians and publicists quote each other rather than the historical primary sources.

A million victims are looking for the perpetrators

There is no disagreement about the Daugava as a rifle trigger between people who have opposing views on whether the Finns wanted to use the rifle at all. The disagreement is about how the Finns hoped to exploit the opportunities opened up by the Germans' attack on the Soviet Union. It had previously attacked Finland and forced Finland into a peace treaty that was destroying it. That was to give up 12% of its territory to the Soviet Union and to remove its population from there, which represented 20% of the country's population. It was difficult for Finland to feed this population, and its population in general, because it was being deprived of a part of Finland that was at the same time the most industrially developed and, in Finnish conditions, the most suitable for agriculture, because it was situated on the southern border of the country. There is no dispute that the Finns considered such a treaty to be a robbery, with no legal or moral force behind it. There was only physical force, i.e., the superior strength of the Soviet army, which the Germans put under question.

The Germans' attack on the Soviet Union gave the Finns hope of at least partially shaking off the peace treaty imposed on them, which in principle could be achieved in two ways. One, the one actually tried, by fighting on the side of the Germans. The other was by not fighting on the side of the Germans if the Soviet Union promised to "pay for it" by including a revision of the 1940 peace treaty in the package of peace treaties in line with the overall situation after the war, even if Finland did not take part in the war. Of course, to get such a promise from the Soviet Union the Finns would have to scare the Soviet dictator Stalin that the Finns were indeed a great threat to the whole Soviet Union, if only by their proximity to the country's second-largest city, Leningrad. But proximity in itself is nothing if the Finns are weak and soft. Therefore, they had to demonstrate how strong and fierce they were in order to realize any further goals. That is to say, that they had got weapons from the Germans and were prepared to fight alongside them.

Both courses of action could succeed or fail. The failure of the first option is known from real history. The second option even had two weaknesses. One was that the Soviet Union would regard promises made to the Finns in a moment of danger as non-binding, just as the Finns regarded their peace treaty with the Soviet Union as non-binding. The other was that the Germans would not only be offended but would retaliate for having been fooled by an unfulfilled promise of fighting on their side.

So the Finns fought, but not always and not everywhere to the full. The war put them on the losing side and forced them to pay for it, both in further deprivations of territory and in US dollars. On the one hand, after the war, there were ears ready to listen to their stories that they had fought only a little and only for justice, not for foreign lands and the like. On the other hand, there are mouths even today that curse the Finns for the way they fought and how they are now making excuses for it.

The voices blaming or excusing of the Finns run as high as one could imagine a mountain with at least 600,000, but perhaps as many as 1.5 million, corpses. This represents the citizens starved in the Leningrad blockade, not counting the soldiers, not counting the direct victims of warfare and not counting those whose deaths corresponded only to the increase in the average death rate during the war. Because of this series of assumptions, there is no one specific number of victims of the blockade, but it is certainly a large number. There might have been no such casualties if the Soviets had remained in possession of the shores of Lake Ladoga, where the Finns had been for several years. From there, the Soviets would have been able to supply enough food across the lake to Leningrad. However, to be able is not the same as to want to or to actually do it. It is only hypothetical how the Leningrad blockade would have ended for the Germans without the Finns.

The war that started a week after the war

The Finnish intentions to adjust the 1940 peace treaty with the Soviet Union not by war but by abstention from war are justified by the fact that the attack across the Soviet and Finland border did not start on June 22, 1941. The Finns did not do it themselves and - it is even hard to believe! - nor did they let the Germans do it. There are two ways of interpreting this action. One is that the Finns waited for the Germans to show the strength to which to bow. The other is that the Finns were waiting for the USSR to offer them a price for their neutrality. The two versions are not mutually exclusive, but complementary. The Germans showed their strength by forcing the Daugava, while the Soviets tried to show their strength by massing troops on the Finnish border and, above all, by the air raids of June 25, ostensibly on Finnish airfields, but in reality, on whoever was in the way of the planes. On June 29, Finnish and German troops crossed the border between Finland and the Soviet Union, which had been drawn up in 1940.

Historians and publicists with contradicting opinions on the Finnish intentions do not dispute that the Finns had indeed reminded the Soviet Union of themselves in five ways between June 22 and 25. The first was the appearance of reconnaissance planes over the territory of a neighboring country, but this might not even count, since in this respect both sides acted identically. The second was that the Finns allowed the Germans to begin the blockade of Leningrad on June 22 by laying minefields around its harbor. In order to be able to do this in time for the outbreak of war, German minelayers had already docked on the Finnish coast. The third was also to mine the harbor by dropping mines into the water from planes flying in from East Prussia and landing in Finland to refuel. The fourth was sending 16 saboteurs in German uniforms to damage the locks of the channel between the White Sea and the Baltic Sea, which the saboteurs were unable to do. The fifth was the Finns, in what warships they had, approaching the Åland Islands, which the Soviet Union demanded should be demilitarized. All these may be called provocations, but they do not reveal their meaning. It could equally well be said that their aim was either war, which actually broke out, or peace, if the Soviet Union were interested in the conditions for peace, that is to say, the price of peace. The unwillingness to pay for peace also made them pay for the war with the starvation of the people of Leningrad, etc., etc.

If you have the possibility and the desire to hear both versions of the Finns' actions in a more extended way in Russian, here are the links and annotations for such lectures. The Finnish action is interpreted by Mark Solonin as an intention to force a revision of the 1940 peace treaty from the USSR without war.

A version much more palatable for the current Russian authorities, but one that has been cleansed of excess propaganda, is presented by Alexey Isaev.

What Latvia sacrificed for geopolitics

Unfortunately, uncovering the geopolitical meaning of the fording of the Daugava River cannot compensate for the damage done to Latvia in the last days of June 1941. These losses have already been pointed out by Neatkarīgā in the series of publications dedicated to the 80th anniversary of the German invasion, according to the order of events in the calendar. Here, first of all, the publication of July 4 "Commemorating the terrible June 29 in Riga and Liepāja" should be mentioned. If the Finns want their 1941-1944 war with the Soviet Union to be seen as a separate war, coinciding only in time with the German war against the Soviet Union, then so be it: let us revisit the same events in a different context.

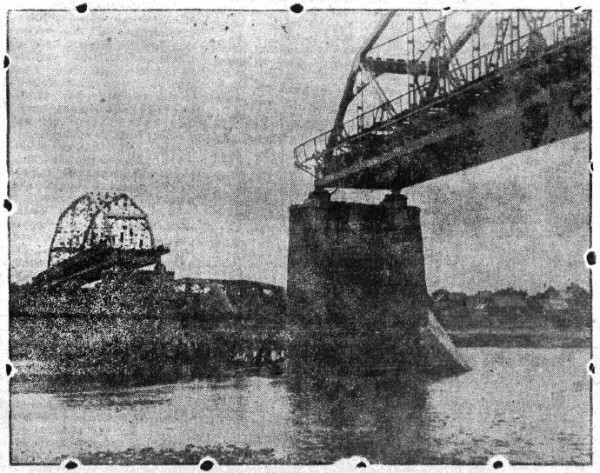

Now Liepāja has to stay on the sidelines, because the story is about the Daugava bridges in Riga, Jēkabpils and Daugavpils. The fight over them caused heavy damage in Riga and Daugavpils, but in Jēkabpils the bridge itself was the biggest sufferer, if you compare the events in Riga, Daugavpils and Krustpils/Jēkabpils.

There is no reason not to believe that in the direction from Jēkabpils to Krustpils the Germans crossed the Daugava as described by the just restored Jēkabpils Vēstnesis on July 31, 1941. On page 1 it shows a photo of the destroyed bridge, and on page 2, under the headline "Last moments of the Red bandits in Krustpils", it tells us that on June 27 "in the early morning hours, suddenly a whirlwind fire was lit. The artillery and other classes of weapons from the direction of Jēkabpils very accurately found the places where the 'invincibles' had set up. Soon they did not hold out and retreated in disorder, leaving many damaged cars, weapons and everything else... At 7 o'clock (present time) two deafening crashes sounded and - the middle truss of the bridge fell into the Daugava. (...) The blowing up of the bridge did not, however, stop the movement of the German army. After a short while, the German units were already moving across the Daugava with their special devices, chasing the last Reds." It was counted that 25 houses were burnt and 20 destroyed in Krustpils, 6 inhabitants were wounded. Jēkabpils Vēstnesis did not give such an account for the Jēkabpils bank.

The main target of the Germans in the territory of Latvia was Daugavpils on the way from East Prussia to Leningrad, i.e., the bridges across the Daugava there. This objective was brilliantly achieved. Magazine Laikmets described this success as "On the morning of June 26, a sudden storm of war swept through the city. Supported by artillery and airpower, an attack by German armored vehicles begins. The battle is fierce but short. At about 10 am, the last Bolshevik combat units leave the town at high speed, and at lunchtime, the inhabitants joyfully greet the bearers of freedom, the German armed forces." How great a success for the Germans, how great a failure for the Soviet army. Soviet propaganda in the 1966 book "The Struggle of the Latvian People in the Great Patriotic War" tried to cover up this failure with the piquant detail that "the main role in the capture of the bridge was played by shock troops... operating in Red Army uniforms. The saboteurs, posing as wounded Soviet soldiers, crossed the bridge, attacked the bridge guard posts from behind and seized it." Unfortunately, this was only the beginning of the battle for the bridges and it was not the bridges that fell victim, but the city. To quote Laikmets, in the second half of June 26, "fires breaks out in several districts of the city. The fire spreads rapidly in the high winds, and soon the whole of Daugavpils is a single sea of flames. For two days this fire rages." Its further consequences came in the autumn of 1941 in the form of diseases, fueled by the conditions in which the homeless people of Daugavpils had to find shelter.

The fight for the Daugava River in Latvia was brought to an end by the burning and collapse of the St. Peter's Church tower on June 29. Unfortunately, this is not just about one tower of one church. A third of the Old Town was destroyed, the great manuscripts in the Riga Town Hall were burnt, and many other bad things happened while the Germans had long since crossed the Daugava according to their blitzkrieg calendar, and the Finns were at that very moment crossing the border of the Soviet Union.

It would be too much to say that the Finns went to war against the Soviet Union only because the Germans gave them the news of the capture of Riga, in accordance with the ancient custom that the best gift and bribe is the heads of enemies. However, this kind of link between the fates of the Latvian and Finnish peoples is worth noting.

*****

Be the first to read interesting news from Latvia and the world by joining our Telegram and Signal channels.