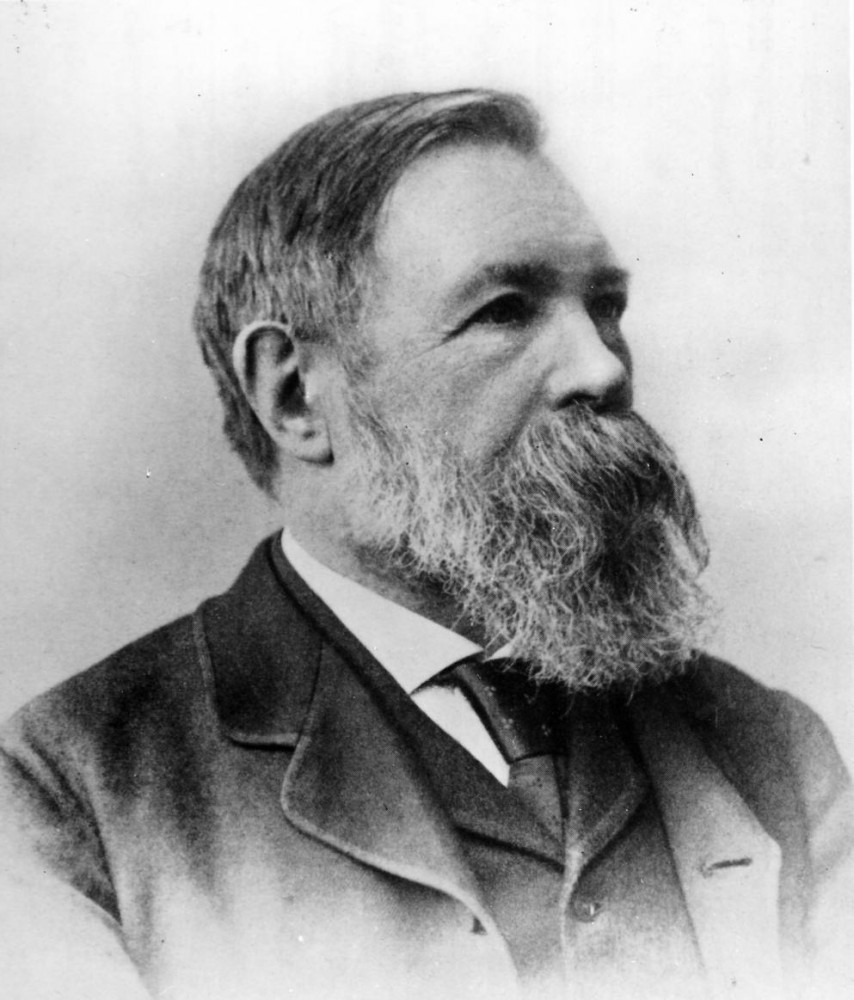

Friedrich Engels as Paul the Apostle of the Marxist faith

Last Saturday, the world quietly and modestly celebrated the 200th anniversary of Friedrich Engels. The younger generation does not know this person at all, and when walking along Stabu Street in Riga, they do not even realise that for half a century the street bore the name of this German thinker. But it should be known, because the ideology, which the world once became acquainted with thanks to Engels, is becoming popular again.

Sometimes conservative people call the so-called left-wing liberals cultural Marxists. Let us not analyze the correctness of this notation, let us simply acknowledge that the modern left movement has an unquestionable phylogenetic link with Marxism. Given the role of Marxism in 20th century history and its growing influence on the modern world, it is worthwhile to find out where the special charm of this ideology lies and who is its ideological father.

Who is the father, who is the godfather?

The second question should be the easiest to answer. If it’s called Marxism then it is clear that the "father" is Karl Marx. But let's not rush to conclusions. The main work of Marx's life is the book Das Capital. Sometime during my studies, I for some reason bought it and even tried to read it. It still stands on my bookshelf as a relic of my youth. Today's Marx researchers almost unanimously believe that Das Capital is a very densely written, boring book that is extremely difficult to read and understand. Many admit that even when forced by professional requirements they still could not read it through. Even among convinced Marxists, it will be difficult to find someone who has waded through it to the end. So why is Marxism so vividly inscribed in human history?

Because it was Engels that turned it from a rather marginal idea into an extremely popular movement. Marx himself did not enjoy widespread acclaim during his lifetime. It was only thanks to Engels that the working class learned that it had been oppressed and that there was this great book, Das Capital, that scientifically described this oppression. The main historical contribution of Marx's Das Capital is in today's unshakable and uncritical belief in the "scientificness" of the social sciences. The more numbers and references in the text, the more scientific it is, that is, the more accurate it is in the last resort. Marx's Das Capital is literally bursting with numbers and references.

The natural desire for justice

From time immemorial, the greatest minds of mankind have noticed that society is not built quite justly, and there has always been a desire to create a fairer system. If not on earth, then at least in heaven. But Engels revealed to the public that there was a terribly clever book (so clever that no one could understand a thing) that scientifically revealed where the root of injustice was to be found. It turns out that capitalism has created an unjust society of exploiters, which can be destroyed by the proletarian revolution and replaced by a new, classless society where everyone "will be equal".

Millions of people wanted to believe that such a just (equal) society without oppressors and the oppressed was possible. This belief was "scientifically" based on the thick, unread volumes of Marx's Das Capital. In order for an unpopular, difficult-to-understand book to become the basis of a widespread belief, one needs a promoter of that belief. Paul the Apostle was practically that in Christianity. In Marxism, this function was performed by Engels, who, unlike Marx, was a talented writer and polemicist. His two interesting, easy-to-understand and sometimes even ironically witty books, The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State and Anti-Dühring, are at the heart of the ideas that modern left-wing radicals have taken and added to their arsenal.

The changing position of power and subordinate

It is clear that those who preach of today's classless society of universal equality do not refer to Marx's Das Capital because not much is left of the "scientificness" of Marx's teachings. It is quite difficult to put the proletariat as the vanguard of human progress because industrial workers, like farmers and any other manual workers (as opposed to urban intellectuals) today are the main opponents of "progress" (Trumpists). It is just as difficult to sell the idea of the imperative need to liquidate private property. On the other hand, if private property is not touched (liquidated), then Das Capital's main "discovery" about the added value that is appropriated by [destroyable] exploiters becomes meaningless.

So what's left? The idea that the historical development (progress) of the world is determined by economic changes, which in turn is driven by the struggle of the oppressed class against the ruling class (oppressors). Today, this idea is embodied in viewing any phenomenon through the prism of the "position of power" and the "subordinate position". The source of this point of view, which is so popular today, is precisely the two books of Engels already mentioned, which are the basis of the later doctrines of so-called Marxism. "The so-called", because, as we can see, we should talk about Engelsism rather than Marxism. This, however, shows the importance of the biblical knowledge that in the beginning there was a word. Marx's surname turned out to be much more suitable for describing the broad human movement than Engels' surname, so humanity will talk about Marxism for a long time, while Engelsism would hardly be considered.

If in his book The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State, Engels carefully describes the historical development of production, the division of labor, the formation of classes, the class society, and the state as the guarantor of the interests of these classes, then in Anti-Dühring he extends this logic of the development of society to morality, which, in Engels' view, is also classist, and to the rights which, by remaining classist, underlie inequality. All of this "class division" today may seem infinitely archaic when viewed from 19th century class positions, but today's Marxists-Engelsists speak in seemingly completely different class categories. For them the oppressed are various minorities - dark-skinned people, homosexuals and those dissatisfied with their gender, women, immigrants, the poor and anyone else who feels oppressed. All would be well and good, because the oppressed really have to be defended and standing on the oppressed side is always morally correct, but there is one thing that must be noted.

There is an extremely fine and elusive boundary when "oppressed" and "oppressors" change places. Modern Marxists-Engelsists should check every day whether this limit has already been crossed. Maybe they have already moved from the "oppressed" class to the "ruling" class, and it's time (as in the early days of Marxism) to start defending Pittsburgh's "poor workers" who vote for Trump? But perhaps they, like the Soviet Bolsheviks, are so fond of the sweetness of power that they want to remain in positions of power and only stand up for "equality" and the defense of the oppressed in words? It turns out that being in a position of power is very comfortable and pleasant, whether this placement is based on Marx, Engels, Simon de Beauvais, Slavoj Žižek or Nelson Mandela. That is something that we should not forget even for a moment as we commemorate Engels' 200th birthday.