Advancements in medicine: a child with epilepsy undergoes a unique surgery in Latvia

Epilepsy causes seizures of varying severity that can start unexpectedly, for example in the street or at night, and for many years now, doctors and scientists have been looking for ways to cure epilepsy. Especially in cases where medication does not help to prevent epileptic seizures.

Doctors at the Children's Hospital have performed a unique surgery for Latvia on an epilepsy patient to find out which part of the child's brain is developing the disorder that causes the seizures and decide on the most appropriate treatment tactics.

Doctors learn new methods for epilepsy examination

Epilepsy is a disorder of the central nervous system that causes seizures of varying severity, from moments of unusual sensations to loss of consciousness and prolonged intense convulsions. The disorder can start at any age, there are several possible causes and the method of examination is usually electroencephalography.

"The brain is a complex organ, its surface is not smooth and several areas of the brain are located deep inside. With electrodes attached to the head during electroencephalography, we cannot catch the electrical signals produced by these deep brain areas," says child neurologist and head of the Epilepsy and Sleep Medicine Centre at the Children's Hospital, Jurģis Strautmanis. The doctor notes that there are several types of epilepsy, including those where seizures originate in one area of the brain and then spread further. In these cases, medication is often ineffective, but surgery can help. "But we need to know exactly which area of the brain needs to be operated on. If doctors have hypotheses about which deep brain structures might be the culprit, they can test these hypotheses with stereo electroencephalography," continues Jurģis Strautmanis.

Doctors at the Children's Hospital have now performed this complex and expensive method of examination, which gives many epilepsy patients hope of a seizure-free future.

The patient has already gone home after the examination

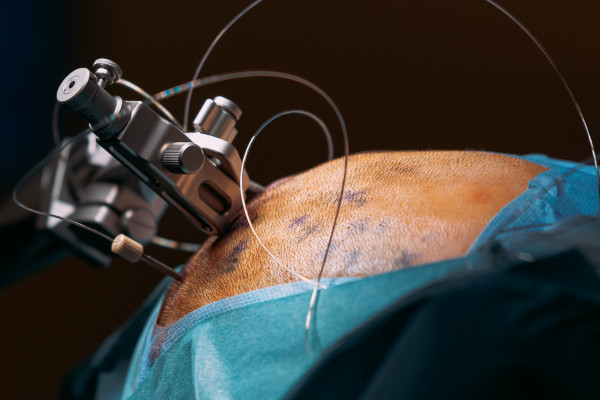

Last week, doctors at the Children's Hospital used this new technique on an epilepsy patient, implanting special electrodes into deep brain structures to obtain stereo electroencephalography measurements. It was the first operation of its kind in Latvia and it went smoothly, the Children's Hospital said. The patient has already had the electrodes removed and the child has gone home. The precise, minimal results of this examination will allow doctors to choose the best treatment tactics.

Child neurologist Jurģis Strautmanis says that stereo electroencephalography, or SEEG for short, is not a new technique, having been invented in the middle of the last century and developed already then in the USA, Canada, France and other countries. However, due to the complexity and ethical considerations associated with the initial version of the method, it was slow to gain popularity. Stereo electroencephalography only became widely used in this century.

To precisely insert electrodes into areas of the brain that are located deep inside, a doctor needs knowledge, skills, technology and funding.

Europe's leading clinics specializing in epilepsy surgery in Italy and France perform only a few dozen such operations a year. Children's Hospital should perform around ten or more so-called deep electrode implantation operations a year, Children's Hospital neurologists and neurosurgeons estimate.

Weeks of preparation

Bassel Yaacoub Wehbe, neurosurgeon and senior physician of the Department of Neurology and Neurosurgery at the Children's Hospital, explains how the surgery was performed:

"The operation to insert 12 electrodes into the deep brain areas using a neuronavigation device took about four hours to complete, but the preparations took us several weeks of hypothesizing and making precise calculations. This reflects the complexity of the operation, which also had to be preceded by a weighing of the risks.

We have succeeded, we are very satisfied. These operations are not just for children, they can help many adult epilepsy patients. They can be performed from the age of three."

After the special electrodes are implanted, measurements are taken and, depending on the frequency of epileptic seizures, recorded over a period ranging from a few days to several weeks, when the electrodes have to be removed. Removing the electrodes is a simple manipulation, the doctors say. The precise results of the stereo electroencephalography not only show which area of the brain is causing the epileptic seizures, but also help to decide whether further surgery is possible and to predict what the outcome might be. Optimally, after the second operation, the patient no longer has epileptic seizures. However, the medics point out that the results do not always show that such an optimal solution is possible. "With the implantation of electrodes in the deep structures of the brain, SEEG measurements and possibly the next operation, we can say to the child and his parents that we have done everything that modern medicine can do for epilepsy patients who are not helped by medication," says Jurģis Strautmanis.

The operation was made possible thanks to funds donated to the Children's Hospital Foundation. The doctors at the Epilepsy and Sleep Medicine Centre at the Children's Hospital and the patient's family would like to thank all the donors.