Lawyer Mārtiņš Kvēps: And then Meroni simply took all the money that was in Ventspils. A very large sum.

In the Lembergs trial, all the witnesses that the parties wanted to cross-examine during the appeal have been questioned.

In the first instance of this trial, witnesses took years to be questioned and some witnesses were questioned for months, but in the appeal instance, witnesses took only a few hours to be questioned.

It should be recalled that at the first instance, 100 witnesses called by the prosecution were cross-examined, whereas the court agreed to call only three of the witnesses called by the defense.

However, at the appeal instance, only three defense witnesses were examined, as the prosecution did not propose any new witnesses, while the defense refused many of the original witnesses in order not to prolong the criminal proceedings.

Thus, Aivars Lembergs' former friends and later enemies, the millionaires Ainārs Gulbis (see here) and Jūlijs Krūmiņš (see here), were cross-examined at the appeal instance.

But the third witness questioned in the appeal was the current lawyer of the elite Mārtiņš Kvēps.

From friend to number one foe

The Lembergs trial shows many examples of close friends becoming implacable enemies over time; of confidants betraying because they calculate that betrayal is materially more profitable; of helping someone being repaid by plotting, etc.

The above is mostly evident from the way in which Aivars Lembergs' relations with the people he was once closest to changed between the mid-1990s and early 2008, since it was in early 2008 that the Prosecutor General's Office created the version that Aivars Lembergs had extorted shares and capital from his former friends in the early 1990s, who later became his enemies.

However, there are also several episodes in the so-called Ventspils transit business war of other participants going from trust and friendship to open hostility. Latvian lawyer Mārtiņš Kvēps, who gave evidence in the appeal instance of the Lembergs case, also followed this path in his relationship with Swiss lawyer Rudolf Meroni.

A friendly group

Mārtiņš Kvēps was the lawyer and representative of the so-called Lembergs opponents - millionaires Oļegs Stepanovs, Olafs Berķis, Igors Skoks and Genādijs Ševcovs - from the very beginning of the so-called Ventspils transit business war, from the end of 2004.

But the Prosecutor General's Office also engaged him as a specialist translator for the Lembergs criminal case.

As Kvēps testified in court, he became a specialist translator in criminal proceedings not only because he had a very good command of English (he had studied at a US university and interned at US law firms) and special knowledge of English legal terminology, but also because it was Rudolf Meroni who wanted to see him as a translator.

"Yes, because when Mr Meroni informed the Prosecutor General's Office that he was finally ready to be honest, to testify about what he had helped Aivars Lembergs to do, and since he did not speak Latvian, there was of course the question of the person who could help translate what he said for the prosecution. And it was very important for Rudolf Meroni - we had a good relationship with him at that point - that the translator was someone he trusted. And also, well, that this person was competent in legal matters, so that what he said was translated as accurately as possible. It was Meroni's wish that I should be the translator. I had no relationship with the Prosecutor's Office before that, I didn't know the prosecutor [Andis] Mežsargs or anyone else. Neither I myself applied, nor the prosecutor's office specifically sought me out. It was Meroni's initiative. The Prosecutor's Office accepted it as reasonable," Kvēps testified. No one paid him for his work as a specialist translator.

In fact, the "Lembergs opponents" quartet - Stepanovs, Berķis, Skoks and Ševcovs - had such good relations with Meroni at that time that he fully trusted the main lawyer of the above-mentioned quartet and appointed this lawyer as a translator in cooperation with the Latvian Prosecutor General's Office. The Latvian Prosecutor General's Office, for its part, did not see any conflict of interest in this situation. And then the whole friendly group - witnesses obviously hostile to Lembergs; their lawyer; Meroni, who managed the assets of both these "opponents" and the "Lembergs family"; prosecutors of the Prosecutor General's Office; employees of the Constitutional Protection Bureau - gradually pushed forward the Lembergs criminal proceedings.

He wants to make tens of millions

"This is how I met Meroni - the first person I met in Ventspils business was Oļegs Stepanovs. One of the big owners. Then I met the others - Igors Skoks, Olafs Berķis, Genādijs Ševcovs, that is, the managers, the officials of Ventspils business, well, not all of them, but a large, very large part. And since all the legal structures behind which the big owners of Ventspils were hiding were mostly Meroni's, my acquaintance with him was both inevitable and natural, because he personally managed all the companies. He also represented offshore. There were shareholders' meetings, there were Supervisory Board meetings, that's how we got to know him," Kvēps testified.

But a few years later, a feud broke out between Meroni and Kvēps, because a feud arose between Meroni and Kvēps' clients, the "Lembergs Opponents" quartet.

For example, former Ventspils Nafta board members Igors Skoks and Genādijs Ševcovs found it difficult to enforce their ownership rights in JSC Ventbunkers due to opposition from Meroni, which led to legal proceedings against the Swiss man in both Latvia and Switzerland, which, as Kvēps testified, were successful.

"With the help of a Swiss lawyer we were able to initiate criminal proceedings which almost resulted in the criminal prosecution of Meroni," said Kvēps.

"It was clear to everyone in Ventspils for a very long time that the Ventspils oil product transshipment business had to be sold, sold. And sold to those who control the cargo flows, who own them. For geopolitical reasons, Ventspils can no longer develop this business; there is only bankruptcy on the horizon. At the same time, when I worked there, the business was still valuable enough, now it is probably worth scrap. Well, in order to sell something to somebody, the ownership needs to be legally formalized. What Meroni was planning, and what he told me this personally - we had countless conversations, even arguments before - was that he wanted to make a lot of money out of this sale, tens of millions of euros. And he understood very well that if he gave people back what they own, if he got all the paperwork right, nobody would pay him any millions. So he fought to the last. So that no man would have any real proof of ownership until the end - everything would be his. He had come up with all sorts of strange ways that he alone could vote and make decisions for everyone - including Igors Skoks and Genādijs Ševcovs. He had appointed himself the final arbiter, so to speak. Well, that was totally unacceptable from a legal point of view. We hired very good trial lawyers in Switzerland, who succeeded both in bringing a criminal case for what he did. And he also lost the trial because we asked, well, so that you understand their position, we went step by step. We sued him first for him to admit that those two people [Igors Skoks and Genādijs Ševcovs] were his clients, for him to give a full accounting as a property manager - what he did, why he did it. He lost that trial. He was forced - Swiss lawyers' fees are very, very large - he had to pay everything, and that was one of the moments when we probably became mortal enemies. Meroni was not used to losing. And, well, yeah, but anyway, as I said, his motivation was to give nothing to anybody, to try to control as much as possible so that he could then squeeze the money out. Then, when there was no buyer, it was clear that, again for geopolitical reasons, you cannot sell anything, not even to the Russians. And then Meroni simply took all the money that was in Ventspils. A very large sum."

"There were three of us, not four"

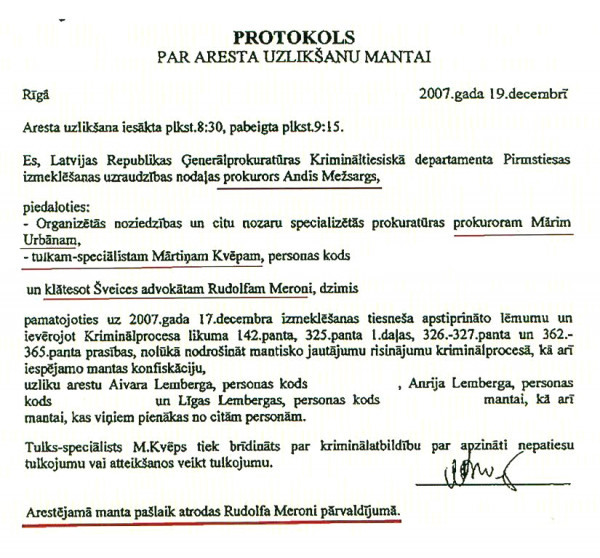

As a specialist translator, Kvēps took part in the drafting and signing of the notorious report of December 17, 2007, on the seizure of property belonging to the "Lembergs family".

It was this protocol that handed over the "seized property" to Meroni for safekeeping, making it the key document on the basis of which Meroni was able to take over the entire Ventspils transit business, which was still thriving in 2007, in the following years.

It is also this document that is the basis for the fact that for more than a year now the Provision State Agency of the Ministry of the Interior has been unable to comply with the decision of the Riga Regional Court and take over these seized assets from Meroni.

Accordingly, the defense asked in the court how the process of seizing the property actually took place.

Kvēps testified that it "took place in Pārdaugava, I think in a hotel. A bit secretly even, so to say".

Asked which persons were involved in the process, Kvēps replied: "I only remember the three of us. There were also people from the Constitution Protection Bureau who provided, let's say, the technical side, the transporting. I suppose that they also rented the premises to keep it secret. But in the actual drafting of the [asset seizure] report, I only remember the three of us - the process facilitator [prosecutor Andis Mežsargs]; I was there, interpreting; and Meroni was, yes, the custodian of the assets."

This is undoubtedly a very interesting testimony, because the protocol on the seizure of the property explicitly mentions that four persons took part in this procedural action - besides the three mentioned above, there was also the prosecutor Māris Urbāns.

However, if the Pārdaugava hotel ABC at Šampētera Street 139a, where the seizure of property actually took place, was chosen by the Constitutional Protection Bureau (CPB) as the place where the procedural action was carried out for "reasons of secrecy", it is interesting to investigate who the owners of this hotel are. They were once the head of the Privatization Agency, Jānis Naglis, and a business partner of the now US-charged Alexander Babakov, Arnolds Laksa. (see, for example, here).

There were no documents

It should be recalled what the "assets" referred to in the minutes of December 17, 2007. The seizures were mostly of "true beneficiary rights" in foreign companies which in turn owned, directly or indirectly, shares in Ventspils' major transit businesses - JSC Ventbunkers, JSC Kālija Parks and JSC Ventspils tirdzniecības osta.

But shares in foreign companies, bearer shares, claims against certain companies and even the obligation to repay debts were also seized. In other words, everything that Meroni instructed the prosecutors to seize as assets of the "Lembergs family" was seized.

Given that the "assets" to be seized were not only shares, which are not difficult to physically bring to the place where the seizure took place, but also "rights" and "obligations", it is only logical that the seizers should have consulted the documents confirming these "rights" and "obligations". Consequently, Kvēps was repeatedly asked this question: had Rudolf Meroni produced any documents proving that the property in question belonged to Aivars Lembergs?

Kvēps testified that there were no documents. Meroni had already sent information to the Prosecutor's Office about the entire "legal structure" of this "asset". "He also drafted the legal formulations and translated them into Latvian with my help," Kvēps testified.

"It was not as if the prosecutor's office came with a big box of papers and presented something to Meroni, because all the papers were already with him." "And there were, of course, now, well, from today's point of view, cases for which there is no property right at all. So there could not even theoretically be any papers produced."

"Well, for example, when the seizure was being prepared, it was the case that Rudolf Meroni himself drew up a list of the assets that were with him, in English. He sent it to me. I translated it into English beforehand and, if I remember correctly, I also showed it to the prosecutor before the actual - well, the asset seizure procedure, let's call it that, or the procedural step - well, of course, so that everybody was aware of what it would all look like, because it all had to be prepared accordingly. Whether you can call that some kind of extra-procedural communication - I don't know, you have to judge that for yourself," Kvēps testified.

Moreover, even after December 2007, Meroni still listed what had to be seized. "But he drew the attention of the prosecution to the fact that some kind of legal enforcement proceedings had been initiated against Meroni himself or his companies. And soon, soon Lembergs will get some more money - in millions. Then something was seized in addition," the witness recalled.

Kvēps believes that Meroni fooled everyone

"The prosecutor's office, which was the driving force behind the proceedings, for very understandable reasons had quite limited information about how it was all set up, how it worked, where everything was. Then Meroni was the one who told them. Who was also doing the legal formulations for the prosecution - what it is, where, what does it look like. And the prosecution, and I myself, had to trust all that to a very large extent. Under the circumstances, well, I'm much wiser now, the world has changed too, the legal framework - true beneficiaries - in the legal field. But on a lot of issues, well, we just trusted what Meroni said. Not everything turned out to be true. On those issues that were personally beneficial to him."

Asked why the seizure was imposed on the "true beneficiary rights" of foreign companies rather than on the actual shares of Latvian companies, Kvēps replied that "I myself thought at the time that that might be enough. The fact that in some cases Meroni had plans of his own, which he did not tell the prosecutor, we all saw only later".

"It was very logical to leave the property where it was. As I said, it was only later that some of Mr Meroni's personal characteristics became known."

"If you think that the rights of the true beneficiary were pushed across the table from the prosecutors to Meroni - that did not happen."

"I can add, because I didn't know it then, but I'm pretty sure of it now, that in most cases, at least in the case of Aivars Lembergs, where the rights of the true beneficiaries did not exist at all, they could not be arrested. They could have seized a shareholding in the companies, but there was no such thing as rights of the true beneficiary, as Meroni put it. Well, in the private law sense - as a right, as a claim, for example. That's a bit different. He was a true beneficiary, definitely, but whether it could be seized - that could be a very serious discussion and doubts. But I myself did not understand and did not know at the time."

"Only the seizure of the rights of the true beneficiary allowed Meroni to manipulate the companies from which those rights of the true beneficiary stemmed with complete freedom and, it seems, impunity. He was completely free to dispose of the shares - as he wished, to whom he wished, to divide, to transfer, to transfer. Always claiming that everything was fine with the rights of the true beneficiaries. And that these manipulations, which he carried out, did not change anything with regard to the rights of the true beneficiaries. I think he did it deliberately so that he could later do what ended the whole Ventspils saga very favorably for him."

"Well, his answer to all the accusations was always that nobody should worry, that the rights of the true beneficiaries were safe, even though the shares travelled wherever he wanted. Well, in my opinion, that is not really acting in good faith or in accordance with the law," lawyer Kvēps testified in court.

*****

Be the first to read interesting news from Latvia and the world by joining our Telegram and Signal channels.